Key-Value Raft & Lab 3

Lab 3 is based on the implementation of Raft in Lab2, and divided into two parts. The goal of Lab3 is to build a fault-tolerant Key-Value database with Raft, so we need to build a service interacting with Raft instances.

Structure

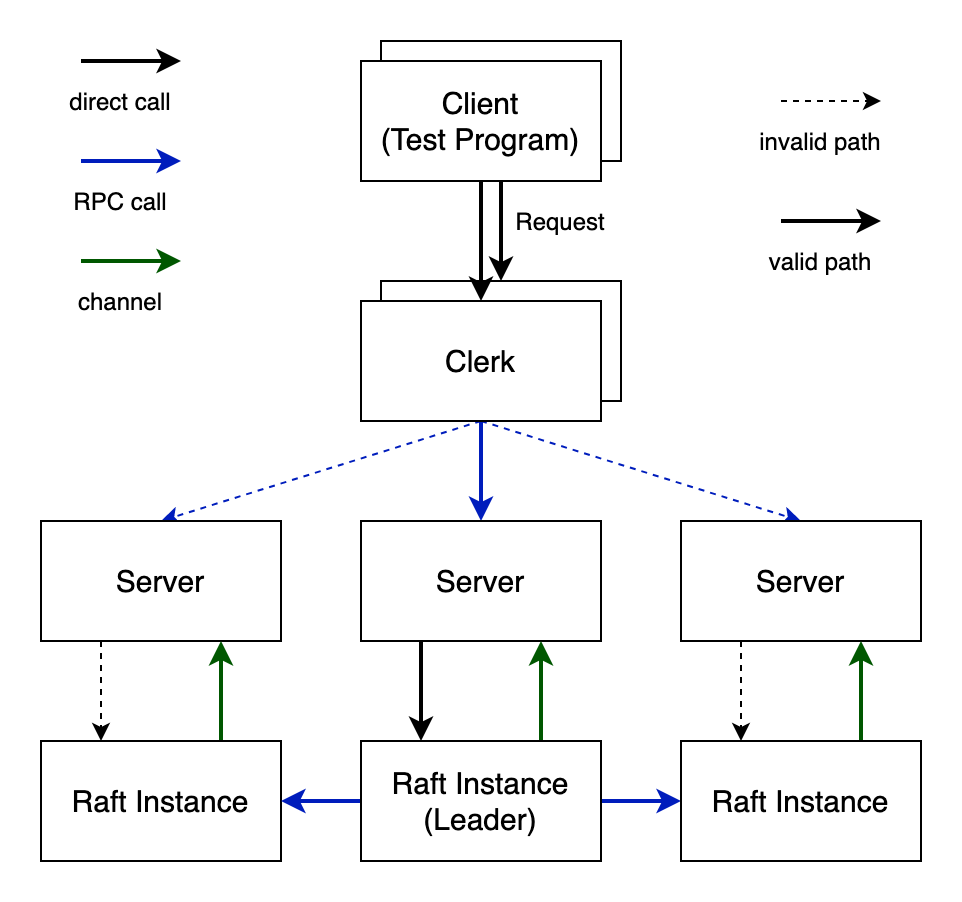

In the KVRaft system, there are three kinds of roles:

- Raft instance: working as the foundation and replicating operation logs

- Server: interacting with Raft instances directly. In real world, each server instance (or program) collaborates with a Raft instance on the same server, so that they can interact with each other directly

- Clerk: sending operation requests to servers, providing interfaces for clients (test program)

There is a simple overview of the whole structure:

As you can see, each client is paired with exactly one clerk, and there could be multiple client-clerk pairs.

Basic rules

There are some rules for our system. Unlike ZooKeeper, no matter what kinds of operations, read or write, should be all directed to the leader. In this way, the clerk should figure out which server connects with the Raft leader by trying each one. It means that though there could be multiple clerks, they all send requests to the same server, if there is no leader change.

In practice, the client, test program, would call server's interfaces of write or read operations directly by invoking related functions. These invocation, however, is blocked, or synchronous. When the test program calls clerk's interface to do an operation, it will wait until the result of the operation returns, and no other operations would be done before this. This is very important, and is also one of our design principles.

The server, however, behaves more complicated. First, not all the servers could communicate with Raft instances directly, or they could, but should not. Only the server that connects with Raft leader could send logs to Raft instance, the leader. Each server maintains its own KV database in memory, as the state machine. Every log it receives will eventually be written into its database, as well as its peers'. We replicate these operations logs to guarantee the status of the state machine should be synchronized with our Raft records. In this way, only the requests related with the committed log from Raft, which makes the operation valid and persisted. In other words, though the server receives requests from the clerk, it should not write these requests to its database until they are committed by Raft. In the above diagram, you can see that the server submit the log to Raft instance (leader), and the Raft instance informs it after the logs has been committed with channel message.

Implementation

Compared with Raft's implementation, it is relatively easy to build the service upon it. However, there is still something requiring notice:

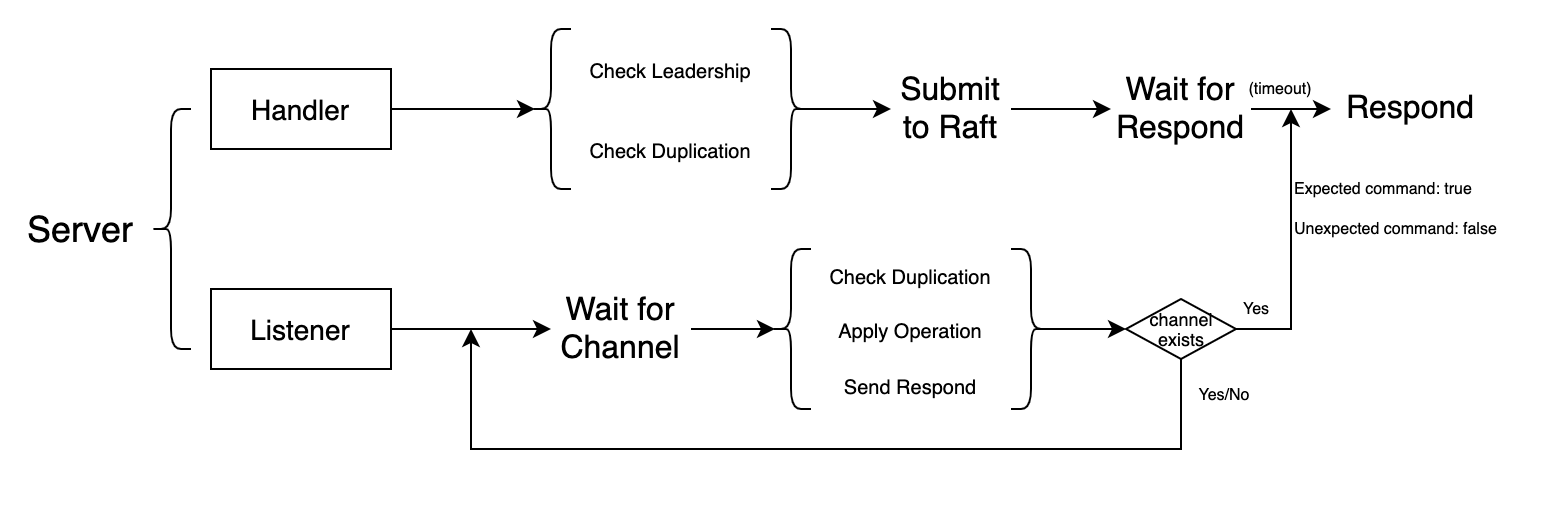

Message communication between server and Raft instance

It is kind of tricky of this interaction between the server and Raft instance. As we discussed above, the message receiving/responding and commitment confirmation are separated. That is to say, the server should wait for the channel message to inform it that related log has been committed, and the operation could be applied to its database. This process, however, could not be done in the function of calling Raft's Start() function, because there is only one channel (external channel) between Raft instance and server, but there could be multiple calls at the same time: they could not hold the channel all together and receive the message exactly they want. So that I designed a separated listener function, starting as goroutine, and making it reads message from the only channel. Once it receives a message from the channel, it will inform related RPC handler and thus the request could be completed and returned.

But how? How to inform related RPC handler? The answer is to use another channel to send message to the handler. Each time the handler submit a log to Raft, a related channel (inner channel) would be created and stored in a map with key equal to the index of the log. The hander just waits for a message for the inner channel. And when the listener receives a commitment message, it would apply related operation to the database, search in the map and send a message to the correct inner channel. Then the handler could receive the message, and finish its job.

There is one thing worth noticing: it is natural to hold the lock when submitting logs to Raft, but it is necessary to release the lock when waiting for message from the inner channel, or the listener could be blocked when operating on the database (deadlock).

Duplicated operation requests

Because of network failure, the requests could be delayed, reordered, and even lost. To be more specific, the network failure would only influence the blue line annotated on the above diagram. We have solved the network failure between Raft instances in Lab 2, and in Lab 3, we need to focus on the network failure between clerk and server.

The first step is to find out the consequence of network failure between clerk and server. That is the clerk could resend the request over and over again, and finally it will get the answer. But unless all other requests except exactly one are lost, the same requests would finally arrive at the server and be submitted to Raft, which is awful, because related commitments could destroy the correctness of the state machine. To avoid this, I make use of the fact that requests are sent to clerk one by one, and in this way, I mark each request with a unique ClientId and a unique SeqId. The ClientId is generated for the clerk randomly at startup, and SeqId is a increasing number generated for each request. In this way, ClientId and SeqId together could exactly identify a request.

I record the latest SeqId for each client in a map, whose key is the ClientId. And every time the server receives a request, it would compare the SeqId of the request with the one in map owing the same ClientId. This is valid because in each clerk, requests are sent in sequence, and unless the former one has been finished and returned, the latter one would not be sent. If the server finds out that the SeqId of the request is smaller than or equal to the SeqId in record, it knows it has received a stale request, and then it would reply immediately without submitting to Raft.

Timeout setting for RPC handler

Remember the truth that a new Raft leader would not commit logs from its former terms? This could lead to a RPC handler to wait for the commit message forever if no new log in the new leader's term is committed. This is deadlock, and we can solve it by setting a timeout threshold for waiting for a message from the inner channel. The RPC handler would return directly and close channel with information telling the clerk to send request again.

However, there is a flaw: The log related to the request has already been submitted to Raft in fact, and it just has not been committed. But with the request resending, the new log and itself would be committed together, and of course duplication commitments read by the listener. In this way, in the listener, I also add duplication detection. I record the latest committed request's identifier: ClientId and SeqId in a map, and each time the listener receives a message from external channel, it will check whether the log's related request has been committed, if so, it will not apply the operation to the database, but still try to find the inner channel and send message, this is because there is only one alive inner channel for these duplicated commitments, and the listener does not know which the channel belongs to, so that it will check every time; if not, the listener could run in the original workflow.

Server running workflow

The workflow of a server could be like this:

Changes to Raft

When implementing Lab 3, I found some flaws in my former design of Raft:

-

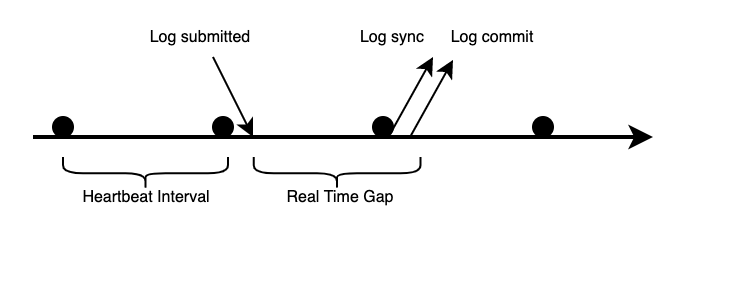

In my former design, the log submission and log synchronization are separated, and no matter a log submitted to Raft leader or not, only after a heartbeat interval passes, will the leader send synchronization RPCs to peers. The workflow looks like:

Because requests from clients are sent synchronously, each request would be confirmed (log committed) would cost heartbeat interval time in length on average, which is 100ms. In Lab 3A, there is a test named

TestSpeed3A, which requires each request should be confirmed in no more than 1/3 heartbeat interval time on average without network failure or other negative conditions, so that I failed on this test.The solution is easy, I just made the Raft leader trigger a log synchronization immediately after receiving a command. And the original workflow was kept.

-

There is a minor bug, or weaker, found during implementation of Lab 3A. In Raft, the leader would start two goroutines to help to send log synchronization RPCs and check commitment periodically, and these two goroutines check whether the Raft instance is still leader and not killed. But after each loop finishes, these goroutines would release the lock and sleep for a while. During there sleep time, there could be such a scenario: the leader loses its leader role, and gains it back in election. In this conversion, the new leader (also the old leader) would start these two goroutines again, just like there are no these goroutines. After the older goroutines weak up, the check is still valid, because they do not know the leader comes into a newer term.

In fact, this bug has no harm to the whole implementation, but it does violate the rule of the minimum interval of heartbeat messages should not exceed 100ms.

In this way, I used the term of leader as a condition when check. Only when the Raft instance holds the leader role, and the term in which goroutine was created is the same as the leader's current term, would the check return true.

-

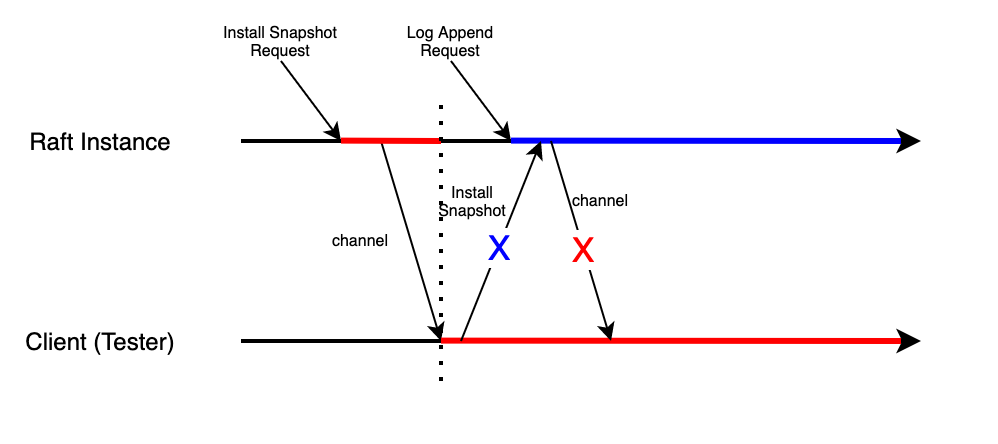

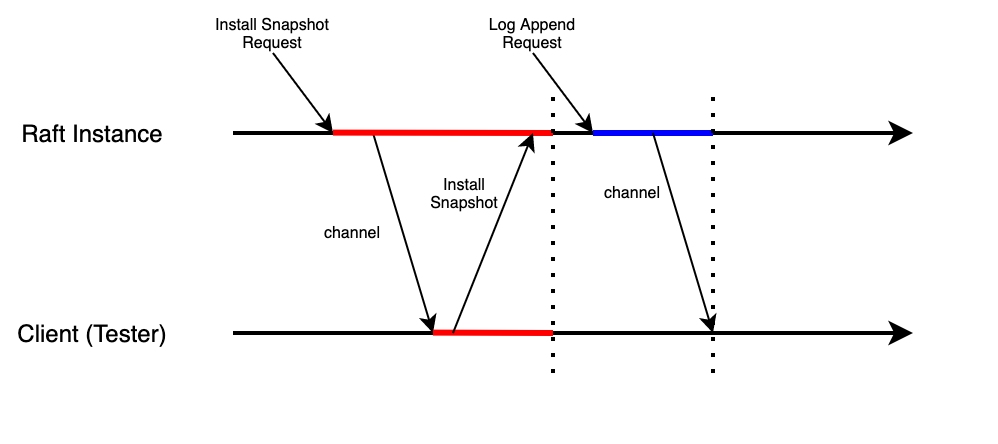

By sending synchronization messages immediately after receiving logs, there appears a new question: there exists deadlock in rare scenarios. How could that happen? This is a diagram to illustrate it:

In this scenario, the raft instance receives Install Snapshot Request from the leader, and it sends a message to client via external channel. Ideally, the client should call Raft instance's

CondInstallSnapshotfunction to install the snapshot, and then everything is done. But If here comes a Log Append Request from leader before the client responds to Raft instance for former received Snapshot-related message, deadlock happens. The red line means the lock holds by the Install Snapshot Request, as well as the scope blocked by the first request. As we can see, because the request releases the lock after sending message to client via channel, the second request, Log Append Request holds the lock, and tries to send a commit message to client via channel. The blue line indicates the lock and scope of the second request. But the function reading from the channel of client is still processing the first request, and it tries to call theCondInstallSnapshotfunction and waits for it finishes. The call, however, would not succeed because the lock is currently held by the second request, that is to say, the first request is now blocked and has to wait for the second request to finish. And the second request is blocked, too. It tries to send message via the channel, but the message it sends to channel could not be read because the function is now processing the message received from the the first request, and it is waiting for the call toCondInstallSnapshotfinishes, so that the second request is now blocked and has to wait for the first request to finish.This scenario is relatively complicated because it involves two parts of Raft, the instance and client. And it did not appear in my former design, because it is almost impossible for this scenario to happen, and only after the change made in Lab 3A, the new log append request could be received before snapshot installation finishes. In past, the snapshot installation could finish in the heartbeat interval, before new log append request comes.

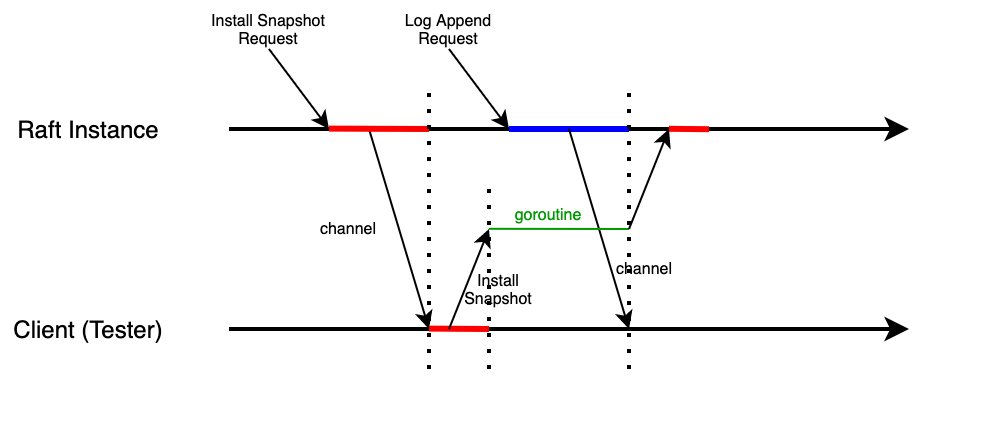

The solution is easy, that is to hold the lock when receiving Install Snapshot Request, and release it after installing the snapshot. Then the diagram should look like:

in this way, there will never be deadlocks in such scenarios, because the snapshot installation is now atomic. The correctness is guaranteed by running Lab 2 tests for multiple times.

in this way, there will never be deadlocks in such scenarios, because the snapshot installation is now atomic. The correctness is guaranteed by running Lab 2 tests for multiple times.[Improvement]

After consideration, however, I found the above solution had a flaw. What if the client fails to call the

CondInstallSnapshotfunction after it reads message from the channel? In this situation, the Raft instance would be blocked forever, even the client process restarts later, it could not recall the function to release the lock. Even though this could happen rarely, it is still a severe flaw to block the whole process. In this way, I came up with a better solution: making use of goroutine to deal with snapshot installation and wait for lock, and let theCondInstallSnapshotfunction return immediately: This solution avoids former situation, because even though the client fails to call the

This solution avoids former situation, because even though the client fails to call the CondInstallSnapshotfunction, the Raft instance would not be blocked. Furthermore, both processes, the Raft instance and client, would not block each other forever after crashing and restarting. The lock of Raft instance does not rely on client's availability any more, which improves the availability of the whole system.

Snapshot

Based on what we have made in Lab 2D, Lab 3B is relatively easy to finish, though there are still some bugs. The most severe one is my misunderstanding of what a snapshot should contain. In my former edition of Raft implementation, I wrongly stored Raft logs in snapshot, but in Lab 3B, I finally realized that it was the database of server that should be put in the snapshot, as well as some metadata to describe the status of server.

By correcting this, basic tests in Lab 3B could be passed easily. And I came into the second dilemma, that is the implementation of interaction between server and Raft instance I mentioned in the last section. The final solution I took in fact weakens the power of Raft, because in that implementation, the server side should verify the snapshot by itself, and the respond from Raft has no use; I also tested the second solution which lock the whole process of installing snapshot, it also worked fine, and the validation totally depends on Raft. In this view, the trade off between the two solutions should be re-estimated.

Though the final solution must check the snapshot by itself, it does not infect its correctness. I make the server side maintain a variable to record the index of last committed log, and use this variable to verify whether the snapshot is out of date. There could be a gap between the server's verification result and Raft's verification result, but it does not matter. In a normal case, if there are no commits inserted in the process, the Raft would judge the same with the server; if there are some commits inserted, it proves that the installation request has already been out of date in the view of Raft, or there could not be inserted commits, and the information the Raft instance uses to make this decision has been synchronized with server's last applied index variable, so that the server could make the same decision.

Optimization

There is actually a point I noticed in my former implementation of Raft requiring optimization. Because my Raft implementation commits logs in batch, and it would hold the lock in the whole process, the server's snapshot request could not be finished before the batch commitment finishes. But to avoid deadlock, the Raft responds immediately after receiving the snapshot request, and starts a goroutine to process the request. In this way, the server could make a lot of snapshot requests, for example:

There are 100 commitments in the batch, and logs are committed one by one. When the 10th log has been committed, the server finds the log size of Raft exceeds the limitation, and it requires the Raft to trim its logs. The Raft responds and starts a goroutine, but does not finish the job indeed. In this way, the same thing would happen when the 11th log has been committed, the 12th, the13th, and so on. The snapshot would not start until the 100th log has been committed, and there has already been 90 snapshot requests (and 90 goroutines waiting). In worst case, the snapshot could be done for 90 times in ascending order, and each time the snapshot with one log longer than the former one would be persisted. It is a great waste of resource and time.

The best way to solve this issue is to allow batch commitment, and it could be done easily in the implementation of server. Unfortunately, the test code of Lab 2D does not support it.

I came up with another way to optimize it in Raft side. I made the Raft maintain variables to record whether there is a snapshot request waiting, the last included index of snapshot, and the temporal snapshot data. Every time the Raft instance receives a snapshot request, it would check whether there has already been a snapshot request related goroutine waiting, if not, it would start a goroutine. Then Raft would check whether the passed in snapshot is more updated than current one (the temporal snapshot, not persisted one), if so, it would update the last included index of Raft and temporal snapshot it maintains. When the goroutine finally wakes up and begins to process the snapshot request, it would use the temporal snapshot. In this way, there is at most one goroutine waiting to process snapshot request, and it could always make use of the most fresh snapshot data.

Another optimization is also a rule, that is never making read side close the channel, but the write side should take care of it. Imagine that, if the server listener receives a command from external channel, and it passes a message via the inner channel. The desired action is that the reader of inner channel receives the message and close the channel, removes related map records. However, there could be a scenario in which the listener receives the same command before the channel has been closed and removed from map, the listener would send the message via the same inner channel again. The listener releases the lock and then try to do this, but the read side quickly holds the lock and closes the channel before the listener sends the message. And finally, the listener would send a message to a closed channel, which makes the test fail.

In this way, the correct design should be that the listener (write side) removes map records after it fetches the channel from map when it still holds the lock. After the listener sends the message via the inner channel, it should close it immediately (the read side could read the message, of course, because the inner channel has a buffer with one log size). In fact, it does not need to do this, because the channel would be released by garbage collection later.

The method is to guarantee all the inner channels would be used only once at most, and they should be removed from map immediately after being picked up from the map to avoid the second pick-up and usage.

The reason I used the channel with buffer is that: in a corner case, say there is a delay of respond from Raft, and the waiting request is timeout. The related inner channel is going to be removed from map and wait for garbage collection. But just before this happens (before the request holds the lock, to be more specifically), the respond comes to the external channel and the listener catches it, holds the lock successfully, and picks up the inner channel to send a message via it. The inner channel just picked up, however, has been abandoned in fact, and if there is no buffer, the message sent via it would not be consumed, and the listener would be stuck there, which forms a deadlock. In this way, with the buffer, no matter the channel has been abandoned for timeout reason or not, the listener would move on immediately after sending a message via it. And because of the guarantee of that an inner channel would be used at most once, 1is enough for the buffer size.

Details could be ignored

At very first, I used Raft's Start function to get the index and check whether it is the leader firstly, and then I initialized a channel and recorded the channel in a map, as well as the expected command. Though working fine without leading any failure in Lab tests, it is still a bad design, or even just a wrong design. This is because the commit of the very command could come to the listener prior to the map-related values set. In fact, it always costs more time for Raft to commit the command than setting these channels and records, but we could not exclude the possibility.

In this way, I changed to use Raft's State function to check whether this instance is leader or not. If so, I would then firstly initialize maps and then invoke the Start function. Instead of using index returned by Start as maps' key, I used client id and sequence is, and the map looks like:

channelMap

|--requestMap1 (clientId: xxx)

|----channel1 (seqId: 1)

|----channel2 (seqId: 2)

|--requestMap2 (clientId: yyy)

|----channel3 (seqId: 2)

|----channel4 (seqId: 3)

I also extracted common functions to deal with map-related operations, including initialization, checking, deleting and internal message sending.

No matter what design we want to take, the key is unmodified: make sure each request has at least one respond. In the former design, there could an internal message for all duplicated client requests; in the latter design, there would only be only one internal message for the latest request among duplicated client requests. So that in both designs, the key could be guaranteed, though in different formats.

Lab Result

Lab 3 is much easier compared to Lab 2, if the implementation of Raft is solid enough. Or it would be a nightmare to face both logs printed by Raft and server side to analysis their behaviors to find out the bug. It is important to believe your Raft instance would always respond correctly, and only then could you focus on the server side.

My code finally passed all the Lab 3 tests in about 450 seconds on my Mac. I have to say these Labs, Lab 2 and Lab 3, helped me make amazing improvement in the understanding of Raft and distributed system. There are no words could be used to describe my feelings after I finally made it, which I used to think I could not finish it by myself at the very beginning.